The vision of covering the Sahara Desert with solar panels to supply electricity to much of the world has circulated for years. The concept feels elegant and almost effortless. However, energy experts, climate scientists, and economists consistently highlight serious technical, environmental, and financial barriers that make this idea far more complex than it first appears.

Why the Sahara Appears Perfect on Paper

From a numerical standpoint, the Sahara seems ideal. It receives some of the strongest and most consistent sunlight on the planet, paired with vast, flat areas and relatively low population density. Popular visuals often suggest that a relatively small portion of North Africa could theoretically meet Europe’s electricity demand. In raw energy terms, the sunlight reaching the Sahara each day far exceeds current global energy use.

Engineers also note that deserts avoid the land competition seen in countries like Germany or the UK, where solar projects compete with farming, housing, and protected land. At first glance, Saharan land appears unused, but this assumption does not hold up under closer examination.

Why Deserts Are Far From Empty

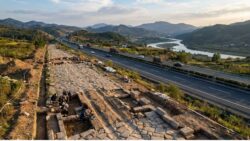

Desert landscapes support delicate ecosystems, nomadic populations, grazing routes, and essential groundwater reserves. Large-scale solar developments require roads, maintenance facilities, transmission infrastructure, and significant amounts of water for panel cleaning and cooling systems.

- Wildlife habitats can be disrupted by fencing and transport corridors.

- Dust and construction place additional stress on fragile soils.

- Traditional land uses risk displacement by industrial activity.

Long before technical or financial concerns arise, the idea of an “empty” Sahara proves misleading.

Heat, Dust, and Climate Side Effects

Climate modelling raises another challenge. Solar panels are dark and absorb more heat than pale desert sand. When deployed across large areas, this added heat can influence local temperatures and air movement.

Simulations of extensive solar farms in the Sahara suggest several outcomes:

- Higher surface temperatures near installations.

- Altered wind patterns and atmospheric turbulence.

- Potential shifts in rainfall across surrounding regions.

Some models even show increased rainfall due to enhanced convection. While that may sound beneficial, deliberate climate alteration raises serious political and ethical concerns, particularly when impacts cross national borders.

Dust as a Constant Efficiency Threat

Dust accumulation presents a persistent operational issue. Fine sand settles rapidly on panels, and even light coverage can reduce output by 10–20 percent. Heavy buildup can cut generation by half.

Cleaning solar arrays spread across thousands of square kilometres requires extensive logistics and, critically, water. Sahara water supplies are limited, already strained, and politically sensitive. While robotic and dry-cleaning systems exist, they increase both cost and complexity.

The Economic Reality of Remote Mega-Projects

Even with falling panel prices, desert mega-projects remain expensive. The panels themselves are no longer the main cost driver. Instead, expenses are dominated by transmission infrastructure, energy storage, security measures, and political risk.

The Challenge of Delivering Power

The Sahara lies far from major electricity demand centres. Transporting power over such distances requires high-voltage direct current lines, which are costly, slow to build, and subject to energy losses.

- Distance to consumers demands long and expensive transmission corridors.

- Cross-border politics require stable international cooperation.

- Security risks make infrastructure vulnerable to disruption.

- Financing conditions increase costs due to higher risk premiums.

Projects like Desertec attempted to overcome these hurdles by linking North African solar power to Europe, but political instability and financial concerns ultimately undermined the initiative.

Storage, Flexibility, and Nightfall

Solar generation peaks during daylight hours and drops to zero at night. Wealthier nations manage this variability with batteries, hydroelectric storage, gas plants, and demand management. Replicating such flexibility around exported desert power is far more difficult.

Proposed solutions include large battery systems, molten-salt thermal storage, or converting surplus electricity into green hydrogen. While technically viable, each option requires heavy investment, often making local solar projects more attractive by comparison.

Political Risk and Energy Independence

Energy supply is inseparable from geopolitics. Recent shifts away from Russian gas highlight the risks of dependence on distant suppliers. Replacing one dependency with another does not eliminate strategic vulnerability.

Within North Africa, some critics view large export-focused solar projects as a form of green colonialism, where local land serves foreign markets while nearby communities face energy shortages. This perception complicates negotiations and investment structures.

As a result, regional strategies increasingly prioritise domestic renewable development, exporting only surplus power to support local industry, employment, and grid resilience.

Why Smaller Solar Systems Are Gaining Ground

While mega-projects dominate headlines, smaller-scale solar solutions are expanding rapidly. Rooftop systems, community solar parks, and hybrid installations combining batteries or backup generators are spreading across Africa, Europe, and the Middle East.

- Reduced transmission needs and infrastructure costs.

- Lower security risks and simpler maintenance.

- Faster deployment and local job creation.

- Greater flexibility as technology evolves.

Rather than relying on a single massive hub, planners increasingly favour interconnected regional systems that share surplus power in multiple directions.

Key Concepts and Realistic Outcomes

Two terms frequently shape this debate. The first is capacity factor, which measures how often a power plant operates at full output. Desert solar performs better than rooftop systems in cloudy regions but still falls short of gas or nuclear plants, increasing the need for storage and backup.

The second is land-use efficiency, or electricity produced per square kilometre. While deserts score well initially, ecological disruption, water use, and grid requirements complicate the calculation.

Comparative modelling often shows that dense rooftop solar combined with offshore wind can outperform Sahara export schemes once political, environmental, and financial risks are included. Desert solar still plays a role, but as part of a broader, diversified energy mix.

In the end, the central question is not whether the Sahara can host large solar farms, but whether doing so makes more sense than deploying countless smaller, closer, and more politically stable projects. The sunlight is abundant, but real-world constraints limit how far that promise can go.