The boat cuts its engine and suddenly the Atlantic goes quiet. Just the slap of small waves, the creak of wood, the squint of half-awake eyes under grey Breton light. A few hundred meters off the French coast, where holidaymakers usually glide by on paddleboards, a group of divers is staring at… nothing. Just a thin, dark line beneath the surface. A line that should not be there.

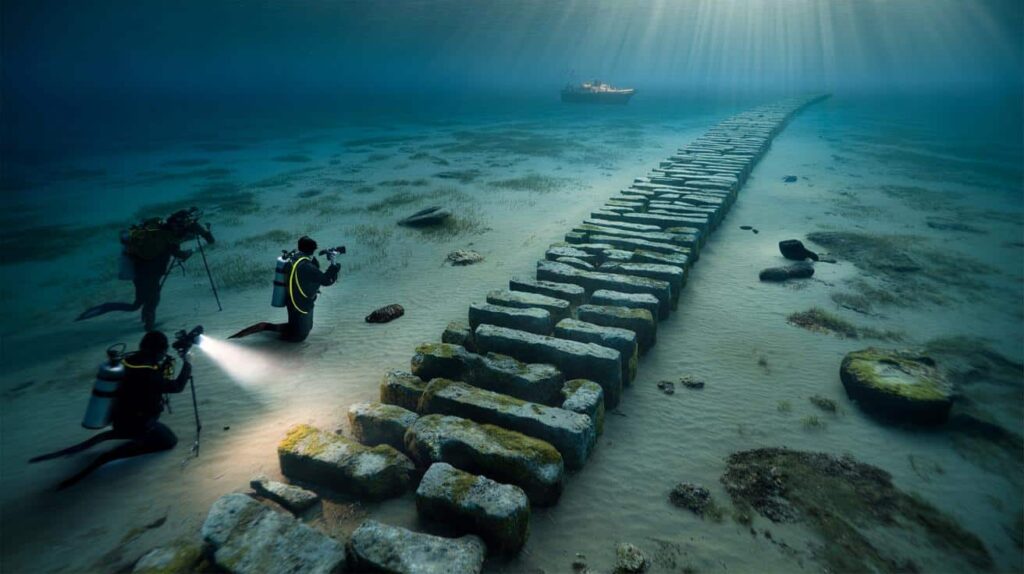

Everyone leans over the side. The diver drops in first, bubbles rising fast, GoPro blinking red. Above, a researcher checks a worn notebook full of sketches, arrows, and dates circled in red. Down below, the camera turns and reveals it: an endless row of stones, perfectly aligned, running like a ghost road across the seabed.

This wall is 7,000 years old.

French Foreign Trade Booms In This Chinese Region With +32.7% Exports In A Year To €432 Million

French Foreign Trade Booms In This Chinese Region With +32.7% Exports In A Year To €432 Million

And it might have been built by hunter-gatherers.

In Bulgaria, a strange rock found by chance in a forest may be the very first star map in history

In Bulgaria, a strange rock found by chance in a forest may be the very first star map in history

A mysterious stone wall sleeping under the waves

From the surface, the site looks like any other patch of rough water off the French coast. A few gulls, a buoy, that’s it. No ruins, no obvious clue that beneath you lies a structure older than the pyramids, older than Stonehenge, older than most of what we call “history”.

The wall itself stretches for hundreds of meters, a low line of stones set deliberately along what was once dry land. Before sea levels rose, people could have walked here, hunted here, lit fires on cold evenings. Now those same stones are carpeted with algae and shellfish, like a forgotten fence in a flooded field.

The strangest thing? It looks planned, not random.

Marine archaeologists didn’t stumble across this by accident during a holiday dive. The structure emerged from a mix of sonar scans, fishing reports, and old nautical gossip passed along harbor cafés. Fishermen had spoken of “something hard” snagging their nets in this area for years, in a tone halfway between irritation and superstition.

When scientists finally mapped the seabed, they saw the outline: a continuous barrier of stones, around a meter high in places. No shipwreck. No natural reef. Just this stubborn, linear anomaly cutting across the old drowned landscape.

Radiocarbon dating from nearby sediments suggests a staggering age: roughly 7,000 years. That places the wall at the very end of the Mesolithic, when much of Western Europe’s coastal populations still lived from hunting, fishing, and gathering.

At first glance, a wall in the water sounds like a defensive structure, something medieval or Roman. But the scale and the date tell a different story. The most plausible hypothesis, according to several researchers, is that this was a “driving wall” for hunting, a tool built by coastal hunter-gatherers to funnel animals or fish.

Picture herds of wild animals migrating along low-lying flats, slowly squeezed into narrower paths. Or schools of fish and marine mammals guided into shallow traps. For people without metal, tractors or nets as we know them, arranging stones into a long barrier was a powerful piece of technology.

It complicates a comforting story we often tell ourselves: that hunter-gatherers just wandered, took what they found, and left no trace.

Did hunter-gatherers really build this? What the clues say

Archaeologists studying the wall aren’t just staring at rocks and guessing. They’re looking at context: the shape of the coastline 7,000 years ago, changes in sea level, known migration paths for animals, and the location of other prehistoric sites nearby. On old reconstructions, the wall sits on a low plain that would have been ideal territory for both humans and prey.

Some stones appear to have been deliberately chosen and stacked, forming shallow V-shapes and slight curves. These subtle bends could have guided animals or fish into a narrower area, where hunters waited with spears or nets. The pattern is what matters here. Nature doesn’t usually lay out a near-continuous, low, linear barrier across a flat landscape just for the fun of it.

One researcher described the moment they saw the full 3D model as a kind of “archaeological whiplash”. You’re expecting boulders, irregular, chaotic. Instead you get a neat, stubborn line that just keeps going. That line follows a contour that would once have been the edge of a wet zone, a perfect place to trap animals who came to drink or forage.

Similar structures are known from other parts of the world. In the Middle East and North America, huge stone “game drives” were used to channel animals like gazelles or bison. Those are later in time, but the logic is the same: control movement, stack the odds in your favor, harvest more food with less risk.

So this French wall might be part of that global story of human ingenuity, just hidden by the sea for millennia.

Skeptics argue that part of the wall could be a natural feature, reshaped by waves and currents. That’s a fair question; the ocean is a restless sculptor. But several sections refuse to sit neatly in the “nature did it” box. Stones are similar in size, alignments are consistent, and there are small side segments that make more sense as extensions than accidents.

Even more telling: the wall lies close to known Mesolithic sites on the current shoreline, places where tools, hearths, and shell middens have already been found. People were here. They stayed long enough, and in enough numbers, to shape their environment.

Let’s be honest: nobody really builds a 700-meter-long line of stones by coincidence.

How underwater archaeology “reads” a 7,000-year-old wall

From the outside, underwater archaeology can look like glamorous diving with extra paperwork. In reality, investigating a structure like this is closer to forensic work in slow motion. Teams map every stone, record exact depths and coordinates, then overlay that with paleogeographic models showing what the area looked like before the sea moved in.

The process starts with sonar scans from the boat, creating ghostly black-and-white images of the seabed. Divers then drop down with cameras, measuring tapes, and tablets sealed in plastic housings. Each stone is logged, photographed, drawn. The goal is to turn a jumble of rocks into a readable sentence.

*Little by little, the wall turns from “weird pile” into “purpose-built tool”.*

If you’ve ever tried to interpret a messy attic years after moving house, you’ll recognize the feeling. Was this box placed here for a reason, or just dumped? Did I keep these books because I loved them, or because there was nowhere else to put them? Underwater, the questions are similar, just colder.

Researchers look for patterns: repeated gaps, changes in stone size along the wall, sections that curve toward what would have been dry ground. They cross-check with animal bone finds, pollen analysis, and even micro-remains of plants in old sediments. We’ve all been there, that moment when a random detail suddenly makes the whole picture snap into focus. That’s what they’re hunting for at 15 meters depth.

What they want is a story that holds together, not just a theory that sounds poetic on a conference slide.

At some point, one of the scientists summed up the emotional weight of the discovery quite simply:

“Every stone you see down there was probably handled by someone’s hands. They had a goal, they were tired, they were cold, they were hungry. This wall is their to-do list, written in rock.”

Through that lens, the structure stops being abstract “prehistory” and starts feeling like a trace of work, of planning, of stubbornness.

For readers, a find like this brings three clear takeaways:

- It challenges the cliché that hunter-gatherers were passive, just following herds.

- It shows how rising seas have swallowed entire chapters of human history.

- It proves that small details on the seabed can flip what we thought we knew about the past.

A submerged wall that changes how we see ourselves

The idea that a community of hunter-gatherers off today’s French coast could organize, coordinate, and build a large stone structure just to direct animals or fish forces an uncomfortable question: what do we really mean when we say “simple society”? The word simple often just means “less documented”. A wall like this, half-buried in sand, is a direct contradiction to the image of people drifting aimlessly through untouched nature.

There’s also a quiet, modern echo in the story. Rising seas drowned this landscape thousands of years ago, transforming a productive hunting ground into a blue emptiness. Today, as sea levels climb again, we’re facing our own version of that slow, creeping line of water. The stones remind us that humans have already watched their coastlines vanish once. They adapted, they moved, they rebuilt.

Walking along the present-day shore, where tourists buy ice cream and kids collect shells, it’s strange to think that under the next horizon lie traces of camps, fires, tools, and maybe more walls. A whole map of human life erased from everyday sight. The people who built that structure never imagined their work would end up under salt water, scanned by sonar and debated on laptops.

That tension between their world and ours is what sticks. You can almost picture them, lining up stones shoulder to shoulder, looking over a wide, open plain with no idea a future ocean would swallow it all. They weren’t “primitive”. They were just dealing with their reality, as we deal with ours.

The wall won’t give up all its secrets quickly. Some will stay lost under sand, algae, and time. Yet even partially understood, it nudges us to rethink where complex planning begins in our species’ story, and to admit that some of our neat categories—hunter-gatherer, farmer, advanced, simple—crumble faster than a stone pulled from the tide.

French foreign trade surges in Chinese Sichuan province with 32.7% export jump to €432 million

French foreign trade surges in Chinese Sichuan province with 32.7% export jump to €432 million

| Key point | Detail | Value for the reader |

|---|---|---|

| Ancient engineering | 7,000-year-old stone wall likely built as a hunting or fishing drive | Reframes how we see so-called “simple” prehistoric societies |

| Submerged history | Structure now lies underwater due to post-glacial sea-level rise | Connects past climate shifts with today’s coastal changes |

| Global pattern | Similar “game drive” systems known from other continents | Shows human ingenuity as a shared, long-standing trait |

FAQ:

- Question 1Where exactly is this 7,000-year-old stone wall located off the French coast?The precise coordinates are usually kept vague to protect the site, but it lies off a low-lying Atlantic shoreline, in waters shallow enough for divers yet far enough to have been dry land in the Mesolithic.

- Question 2How do scientists know the wall is around 7,000 years old?They date organic material trapped in nearby sediments and relate it to known sea-level curves, then cross-check with other archaeological finds from the same drowned landscape.

- Question 3Could the wall really have been made by hunter-gatherers and not early farmers?The timing falls at the very end of the Mesolithic, before full agricultural settlement clearly dominates this region, which strongly suggests a hunter-gatherer or mixed-economy community.

- Question 4Is the wall unique, or are there similar structures in Europe?Comparable “driving walls” and stone alignments have been identified in other submerged areas and upland zones, though each site has its own local twist and purpose.

- Question 5Can the public visit or dive on the site?Access is typically restricted or guided, both for safety and to protect fragile archaeological layers, but museum exhibits and digital reconstructions are increasingly used to share the discovery with a wider audience.