Japan has discreetly begun a high-risk deep-sea operation that could reshape the global supply of critical minerals and reduce the country’s long-standing reliance on China. The initiative reflects Tokyo’s growing concern over supply security for materials essential to modern technology and clean energy. By moving into some of the deepest waters ever targeted for resource extraction, Japan is testing whether advanced engineering can unlock a new, domestically controlled source of rare earth elements while navigating significant technical and geopolitical challenges.

Japan sends its flagship drilling vessel into the deep

The scientific drilling ship Chikyu has departed from Shizuoka, heading toward waters near Minamitori, also known as Minami-Torishima, a remote atoll nearly 1,900 kilometres southeast of Tokyo. Over the course of a month, the vessel will attempt an unprecedented task: continuously pumping mud rich in rare earth elements from approximately 6,000 metres below the ocean surface directly up to the ship. No country has ever carried out this process at such depth on a sustained scale. Japan is effectively testing whether a technological crown jewel can transform an isolated seabed into a strategic mineral lifeline. The mission carries enormous technical uncertainty and equally heavy political significance, as Tokyo seeks to reduce its exposure to export decisions made in Beijing.

Why deep-sea rare earth muds are so important

Rare earth elements comprise a group of 17 metals that underpin the digital economy, green technologies, and modern defence systems. They are essential for electric vehicles, smartphones, wind turbines, missiles, and radar systems. While these metals are not especially scarce in Earth’s crust, they are rarely found in concentrations that make extraction economically viable. Processing them also requires complex chemical facilities and strict environmental oversight. Japan remains heavily dependent on imports, and even after years of diversification, about two-thirds of its rare earth supply still comes from China, particularly for heavier and more strategic elements. A brief export squeeze in 2010 convinced Japanese policymakers that rare earth supply security represents not just a trade issue, but a national vulnerability.

Key technologies that rely on rare earth elements

- Electric motors and wind turbines depend on neodymium, dysprosium, and terbium magnets.

- LED screens and advanced displays use europium and yttrium to produce vivid colours.

- Medical imaging systems rely on compounds made from gadolinium and lutetium.

Minamitori: a small atoll with an outsized resource potential

On the surface, Minamitori is little more than a military outpost with a runway, surrounded by coral reefs. It has no meaningful tourism industry and is home to only a small number of people. Beneath the waves, however, lies a very different picture. Over the past decade, Japanese research expeditions have identified thick seabed mud layers rich in rare earth elements, particularly heavy metals such as terbium and dysprosium. These deposits formed over millions of years as metals dissolved in seawater gradually settled onto the ocean floor, creating a fine, clay-like sediment. This soft texture offers a modest engineering advantage, as it can be vacuumed rather than blasted, though the extreme depth remains the primary obstacle.

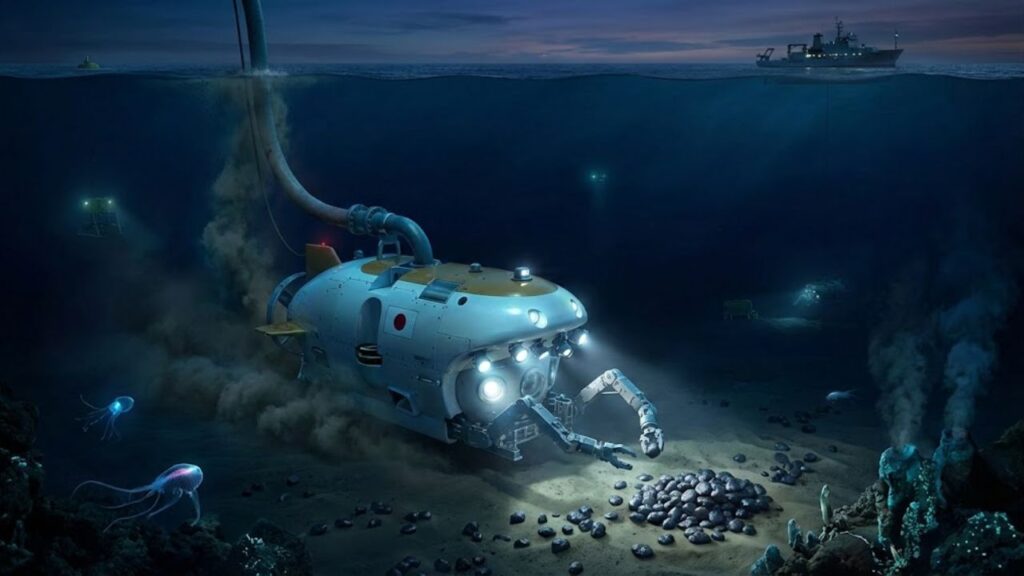

The extreme engineering challenge at 6,000 metres

At a depth of 6,000 metres, water pressure reaches roughly 600 times that of sea level, temperatures hover near freezing, and equipment must endure strong currents alongside crushing force. Chikyu is among the very few vessels designed for such conditions. It uses dynamic positioning thrusters to remain almost perfectly stationary above a precise point on the seabed, even in rough seas. Engineers will lower a long riser pipe to the ocean floor and attempt to pump mud upward in a steady flow. Any blockage, structural failure, or unstable flow could undermine the entire concept of deep-sea mud extraction for years to come. Onboard laboratories will analyse samples in near real time, assessing metal concentrations, particle size, and the effort required to separate valuable elements from waste.

Funding, timelines, and the critical 2027 checkpoint

Since 2018, Japan has invested roughly 40 billion yen into its deep-sea rare earth programme. Officials have deliberately avoided bold public promises and have not released firm estimates of recoverable resources. The current expedition serves primarily as a technology validation exercise. Policymakers and industry partners are seeking answers to several crucial questions: whether the riser system can operate reliably for extended periods, whether flow rates are sufficient for commercial viability, and whether metal grades remain attractive once processing costs are factored in. If the mission proves successful, a larger-scale trial is planned for around early 2027, with any potential commercial production likely pushed toward the end of the decade.

How the project fits Japan’s wider rare earth strategy

Japan has pursued multiple strategies since the 2010 supply shock, when a maritime dispute briefly halted Chinese rare earth shipments. These efforts include backing overseas miners, expanding recycling, and building strategic stockpiles. Despite progress, economists argue that true security requires sources Japan can influence more directly. The deep-sea deposits around Minamitori fall within Japan’s exclusive economic zone, giving Tokyo far greater legal and political control than it has over foreign mines. This advantage makes subsea resources particularly attractive, even as they remain technically challenging.

- China: Supplies 60–70%, especially crucial heavy rare earths.

- Australia: Provides 15–20% through long-term contracts and Japanese-backed processing.

- Domestic recycling: Accounts for 5–10% and continues to grow.

- Strategic stockpiles: Used as buffers against sudden disruptions.

- Subsea deposits: Currently unproduced, with potential after 2030.

Geopolitical implications beneath the ocean floor

The mission unfolds amid intensifying global competition for critical minerals. China has already tightened export controls on several strategic materials, including those used in advanced chips and high-performance magnets. The United States, European nations, and others are actively seeking alternative suppliers, supporting projects from Greenland to Brazil. Japan’s push into ultra-deep waters reflects the same concern: that access to rare earths could become a tool of leverage in future disputes. If Japan demonstrates that deep-sea mud extraction is both feasible and manageable, it could weaken China’s dominant position and alter the balance of bargaining power for countries dependent on imported high-tech components.

Environmental questions still awaiting clear answers

Although the current expedition focuses on technology and geology, environmental concerns remain unresolved. Pumping mud from extreme depths will generate plumes of fine sediment near the seabed and potentially higher in the water column, depending on how waste water is discharged. These plumes could affect deep-sea ecosystems that are still poorly understood. Additional worries include noise, artificial light, and the risk of accidental leaks. Critics argue that regulations for deep-sea mining lag behind the accelerating search for critical minerals. Supporters counter that Japan’s activities occur within its own waters and could be more tightly regulated than operations in international seabed zones. Long-term decisions will likely depend as much on environmental impact studies as on economics.

What “rare earths” and “heavy” elements actually mean

Despite their name, rare earth elements occupy a single row of the periodic table, from lanthanum to lutetium, with yttrium often included. Their similar chemical behaviour makes them difficult and costly to separate. They are commonly divided into light and heavy categories. Light rare earths, such as lanthanum, cerium, and neodymium, are more abundant and mined in several countries. Heavy rare earths, including terbium, dysprosium, and lutetium, are scarcer and far harder to source outside China. The muds near Minamitori appear particularly rich in these heavy elements, which is why they are viewed as strategically valuable despite the high operating costs.

Possible outcomes if the project succeeds or stalls

If the Chikyu mission delivers stable pumping and strong laboratory results, Japan could move toward dedicated production systems, including larger extraction vessels, offshore processing units, and specialised onshore refineries. Such a supply would not replace all Chinese imports but could provide a critical safety valve during crises and supply premium material for sensitive uses like defence and advanced motors. If the project falters due to technical failures, weak grades, or environmental opposition, Japan is likely to intensify other measures, including expanded recycling and deeper partnerships with allies. For companies in Europe and North America, the outcome matters: success could stabilise prices and encourage new manufacturing outside China, while failure would reinforce Beijing’s strong position for years to come.