The first thing you notice is the wind. It is cold, biting, and damp as it cuts across the ridge where Hadrian’s Wall still grips the Northumberland skyline. You take in the stone line so often described as majestic or iconic and try to imagine shining armor, polished shields, and disciplined soldiers watching the northern edge of the empire. For a brief moment, the picture almost holds.

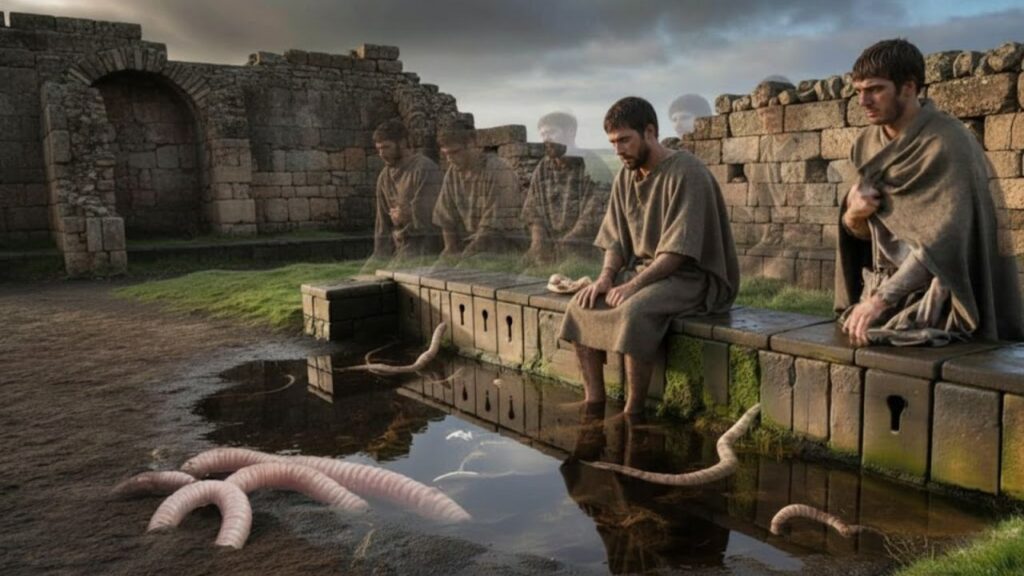

Then the guide gestures away from the ramparts, pointing instead to a low stone structure beside a shallow ditch. “That,” she explains, “was the latrine.” The illusion collapses. You picture dozens of Roman soldiers packed onto stone benches, clothes hitched up, insects swarming, parasites spreading. From here, the empire smells very different.

It becomes clear that much of what we believe about the Wall is built on the wrong side of history.

Hadrian’s Wall Up Close: Toilets, Parasites, and Daily Reality

Stand inside the ruined fort at Housesteads and your attention is pulled outward. Rolling hills, wide sky, and the Wall stretching across the horizon like a stubborn scar. Visitors frame their photos carefully, often cropping out the squat stone latrine only steps away. It is easy to see why. Communal toilets do not fit neatly with ideas of glory.

Yet that dark block of stone tells a truer story of Roman Britain than any monument. Archaeologists have uncovered parasite eggs here — whipworm, roundworm, and likely tapeworm — fossilized traces of soldiers living with constant irritation, pain, and lingering illness. The frontier was not gleaming. It was uncomfortable and unhealthy.

What the Parasites Reveal About Roman Life

Several years ago, parasite specialist Dr. Piers Mitchell and his team examined layers of waste taken from Roman latrines along the Wall. Under magnification, the image of a pristine empire fell apart. The samples showed signs of poor sanitation, contaminated food, and polluted water. One latrine deposit contained dense clusters of intestinal worm eggs — silent evidence of everyday suffering.

Soldiers ate bread tainted with soil, drank from fouled wells, and used shared stone benches flushed by the same narrow water channel. Some relied on sponges on sticks as toilet paper, rinsing them in water everyone else used. The spread of infection required no mystery. Roman discipline did not include germ awareness.

Beyond the Myth of Order on the Empire’s Edge

This is more than an unpleasant detail about ancient plumbing. It challenges the familiar image of Roman order at the world’s edge. We like to imagine the Wall as a sharp boundary between civilization and chaos. The parasite evidence suggests a different divide — one between our expectations and their lived experience.

Roman engineering was impressive for its era, but it collided with habits that have never changed: cut corners on hygiene, confidence without understanding, and ignorance of invisible threats. On paper, the Wall’s toilets were clever. In reality, they failed the people who used them.

No communal latrine is ever cleaned as perfectly as its plans assume.

Why Roman Britain Deserves a Fresh Perspective

Look at how Roman Britain is presented today. Family attractions promise “Life on the Roman Frontier”, complete with toy shields and plastic helmets. Television dramas polish away the grime, focusing on speeches and honor while skipping over worms and stomach illness. The epic version is always easier to sell.

A more honest measure of any society is its toilets. Who could use them, how clean they were, and what happened to the waste. Along the Wall, the answers are blunt. Officers enjoyed better facilities. Ordinary soldiers lined up in freezing communal blocks. Local populations often had none at all. This looks less like a golden age and more like inequality paired with disease.

The empire feels far less heroic once the smell is acknowledged.

How the Polished Story Took Hold

The roots of the myth are easy to trace. Victorian scholars admired Rome’s straight roads and military order. They saw Hadrian’s Wall as a reflection of their own ideals — Rome as an early version of Britain. Latrines full of parasites did not fit that image, so they were quietly ignored.

That inherited lens still shapes how we look today. Standing on the Wall, it is easy to feel pride in a shared past and forget that the men who built it were often tired, undernourished, and frequently ill. Once you imagine a guard doubled over with cramps during a night watch, romance fades quickly.

This does not diminish their strength. It restores their humanity.

Goodbye Hair Dye for Grey Hair: The Conditioner Add-In That Gradually Restores Natural Colour

Goodbye Hair Dye for Grey Hair: The Conditioner Add-In That Gradually Restores Natural Colour

When “Progress” Makes Health Worse

The parasite findings also challenge another assumption — that Roman rule automatically improved health. Research in Britain suggests that worm infections increased under Roman occupation compared with the Iron Age. More baths, aqueducts, and buildings did not mean healthier bodies.

Crowding played a major role. Forts and towns packed people, animals, and waste together. Latrines drained into ditches that overflowed. Manure spread on fields carried eggs into crops. People bathed frequently, but often in water that spread the same infections.

Rome is often shorthand for progress. The Wall’s toilets offer a quieter truth: progress is uneven, and sometimes it fails where it matters most — inside the body.

Seeing Hadrian’s Wall Without the Filter

On your next visit — in person or through images — try a simple shift in perspective. Take in the classic view first: stone, sky, and scale. Then move your attention a few meters to the side, toward the half-ruined latrine blocks most people ignore. Hold both scenes together.

Ask direct questions. Who cleaned these spaces? Who became sick most often? What was it like to sit on cold stone in winter with no privacy and an upset stomach? The Wall stops being an abstract symbol and becomes a place filled with real bodies and routines.

This small change pulls Roman Britain down from its pedestal and back into the mud.

Looking Past the Glossy Angles

Many visitors move through historic sites in museum mode — respectful, distant, and unchanged by what they see. The latrines along the Wall ask for something else.

Instead of chasing flattering views, pay attention to the awkward spaces. Ask guides about disease, diet, and labor, not just battles and emperors. Notice which features get polished displays and which, like drains and sewage channels, barely receive a label.

The least glamorous places often tell the most honest stories.

As one archaeologist remarked on site, “People think the baths and toilets prove how clean the Romans were. What they really show is how much waste they created, and how poorly they understood what made them ill.”

Simple Ways to Rethink the Wall

- Look down, not only outward — give drains, ditches, and latrines the same attention as walls and gates.

- Ask difficult questions — who was excluded from comfort, and who carried the waste away?

- Resist the cinematic image — add dirt, irritation, and constant discomfort back into the picture.

- Follow daily routines — eating, sleeping, washing, and toileting reveal where power really sat.

- Accept contradiction — Rome could build wonders and still fail at basic public health.

What the Wall’s Toilets Reveal About Us

Looking at those parasite-filled latrines, the lesson extends beyond Roman Britain. It exposes our desire for clean, heroic stories, even when the evidence beneath our feet is uncomfortable. We still like to believe that order and engineering automatically bring wisdom and well-being. The Wall quietly disagrees.

Rome arrived with roads and forts, promising structure, and left behind widespread illness. The pattern feels familiar. Even today, impressive projects can rise alongside failing water systems, understaffed hospitals, and broken sanitation.

The true measure of a society is rarely its monuments. It lies in what gets flushed away, who deals with it, and who becomes sick. The Wall still stands, and so do the myths around it. The real question is whether we are ready to listen to what its toilets have been saying all along.

Key Takeaways

- Roman image vs. physical reality — latrines along the Wall contain clear evidence of parasites and poor hygiene, challenging the polished narrative.

- Toilets as power markers — access, cleanliness, and illness reveal deep inequalities within the empire.

- Rethinking civilization — advanced engineering can exist alongside serious public health failures, then and now.