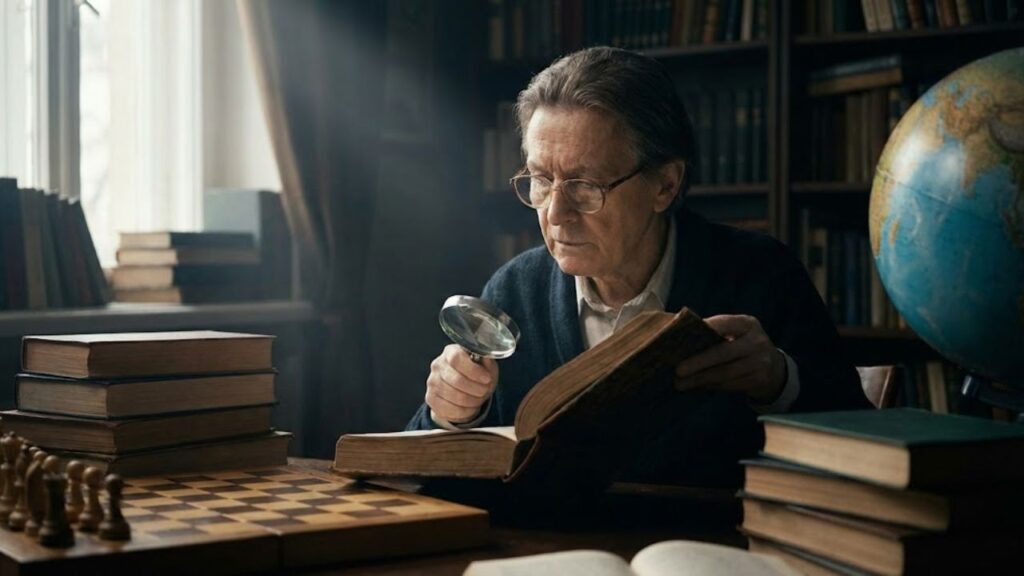

Some people come across as calm, perceptive, and unconcerned with proving their intelligence. That composure is rarely accidental.

Psychological research increasingly suggests that genuinely intelligent individuals tend to share a low-key but powerful habit. It has nothing to do with IQ scores, prestigious education, or cognitive training tools. Instead, it reflects a subtle change in how they relate to others.

The quiet habit shared by highly intelligent people

For many years, intelligence was boiled down to a single number: IQ. A higher score implied greater potential, while a lower one often shaped expectations. Today, scientific research offers a broader view, showing that intelligence extends beyond problem-solving to include self-regulation and interpersonal behaviour.

The French construction giant accelerates its push into Oceania with a €183m takeover in New Zealand

The French construction giant accelerates its push into Oceania with a €183m takeover in New Zealand

Across multiple studies, psychologists have identified a consistent trend: individuals with stronger cognitive abilities are less driven to prove their intelligence. They feel less compelled to dominate conversations, show off knowledge, or “win” debates.

This world-famous psychologist is now certain: wabi-sabi is the best life philosophy, and here’s why

This world-famous psychologist is now certain: wabi-sabi is the best life philosophy, and here’s why

The habit that stands out most is simple yet telling: highly intelligent people stop trying to demonstrate how intelligent they are.

Rather than performing, they rely on emotional maturity. They listen attentively, tolerate uncertainty, and accept that all knowledge has limits, including their own. From the outside, this often appears as quiet confidence, but it rests on refined mental discipline.

Looking past IQ: intelligence as a set of skills

Modern psychology increasingly treats intelligence as a collection of abilities rather than a single trait. These commonly include:

- Cognitive intelligence – reasoning, learning, memory, and problem-solving

- Emotional intelligence – recognising and managing emotions in oneself and others

- Social intelligence – navigating relationships, group dynamics, and trust

A 2019 study published on Science Direct and conducted in China found a link between higher intelligence and more prosocial behaviour. Participants with stronger cognitive abilities reported being more helpful, considerate, and attentive to others’ emotions. They also tended to see themselves as moral individuals, not out of superiority, but from a genuine concern for doing what is right.

Overall, research connects higher intelligence with greater emotional sensitivity, social awareness, and personal ethics.

This does not imply that all intelligent people are kind or ethical. However, it does suggest that, on average, advanced cognitive skills often coexist with a richer emotional and social life. From that combination, the habit of not constantly proving oneself naturally develops.

- Airbus’s biggest rival returns with a €6 billion mega deal for 110 Alaska Airlines aircraft

- “I feel tired of being strong”: psychology explains emotional endurance

- A simple family bank transfer can now trigger a tax audit

- He donated DVDs, then discovered they were resold as valuable collectibles

- A state pension cut is approved, reducing payments by £140 per month from February

- Expert-approved: three words that make you sound more confident in conversation

- Choosing the right wood stove: five key points buyers often overlook

- Hygiene after 65: why skipping daily showers may be healthier than expected

Emotional maturity and the end of performance

Emotional maturity sits at the core of this behaviour. It reflects the ability to respond thoughtfully rather than react impulsively or defensively.

According to research published in the International Journal of Indian Psychology, maturity is closely linked to psychological flexibility. Emotionally mature individuals adjust their responses to fit the situation. They do not interpret every disagreement as a personal threat and are more capable of turning tense moments into productive exchanges.

This maturity becomes visible in everyday situations:

- In meetings, they allow others to speak, ask clarifying questions, and revise their views when evidence changes.

- During arguments, they avoid humiliating others, even when their own position is stronger.

- After success, they resist the urge to seek validation by broadcasting achievements.

Choosing not to prove you are right, even when you are, often reflects higher intelligence rather than weakness.

These individuals are not holding themselves back. They are preserving mental energy, maintaining relationships, and reducing unnecessary conflict, benefits that accumulate steadily over time.

The Dunning–Kruger effect and misplaced confidence

This tendency is closely related to a well-known cognitive bias called the Dunning–Kruger effect. It describes how people with lower ability often overestimate their competence, while those with greater expertise tend to underestimate themselves.

How the Dunning–Kruger pattern typically appears

- Low skill level: strong confidence, little doubt, and a frequent need to prove a point

- Moderate skill level: growing awareness of difficulty, more questions, mixed confidence

- High skill level: cautious claims, nuanced thinking, and minimal need to show off

As knowledge deepens, complexity becomes more visible. This naturally encourages humility and caution. People with greater intelligence are less comfortable making absolute claims and more willing to acknowledge uncertainty.

Those who know little often feel certain; those who know more tend to be careful.

This does not mean intelligent individuals lack confidence. Instead, they place confidence in accurate understanding rather than appearances, leading to more balanced decisions and fewer dramatic assertions.

The psychological benefits of letting go of self-proof

Stepping away from constant self-justification brings several subtle mental health advantages. Research highlights multiple positive effects when interactions stop feeling like tests of personal worth.

- Reduced mental fatigue from not rehearsing arguments or defending ego

- Stronger relationships built on feeling heard rather than judged

- Fewer conflicts as disagreements end with reflection instead of escalation

- Greater emotional calm when self-worth is not tied to recognition

This understated form of intelligence may appear unremarkable at first glance. Yet over time, it quietly shapes careers, friendships, and stress levels.

Self-evaluation: the skill beneath the surface

At the foundation of this habit lies realistic self-evaluation. Intelligent individuals tend to monitor what they know, where gaps exist, and when they might be mistaken. This internal awareness guides how forcefully they present ideas.

A reliable indicator of intelligence is not volume or persistence, but accurate awareness of one’s limits.

This does not always resemble traditional modesty. When evidence is strong, highly intelligent people can speak decisively. The difference is their readiness to adjust when new information emerges.

Practising this intelligent restraint

You do not need formal testing to cultivate this habit. Research points to several everyday behaviours that encourage it:

- Pause before defending yourself and consider whether winning is necessary

- Acknowledge uncertainty with phrases that leave room for correction

- Welcome better arguments as improvement rather than defeat

- Examine your motives to ensure you are adding value, not performing

These small adjustments influence not only how others perceive you, but also how effectively you think, by freeing mental space for learning.

When restraint turns into self-doubt

There is also a limit. Excessive self-questioning can slide into paralysis or chronic doubt. Some highly capable individuals, particularly in competitive environments, experience persistent feelings of inadequacy often labelled as imposter syndrome.

The aim is not to eliminate confidence, but to balance conviction with openness. Intelligent restraint communicates: “I trust what I know, and I’m willing to revise it.”

Everyday moments that reveal quiet intelligence

Consider a workplace meeting. One person dominates discussion, dismisses questions, and reacts defensively. Another shares ideas, invites feedback, and credits others for improvements. The second person may know more, yet feels less need to prove it. Research consistently links this pattern with higher intelligence.

Or think of a family disagreement. One voice pushes certainty, while another says, “I remember it differently, but I could be mistaken.” That response reflects careful management of memory and ego, not weakness.

In everyday life, the most intelligent person is often the one most comfortable saying, “I could be wrong.”

Scientific evidence suggests that if you are becoming less interested in showcasing your intelligence and more focused on accuracy and stable relationships, you may already be practising the defining habit of above-average intelligence.