Archaeologists report that a vast ancient highway, built more than two millennia ago, has emerged from the ground in remarkable condition, prompting modern engineers to reconsider what truly qualifies as a large-scale infrastructure project.

An ancient roadway with surprisingly modern design

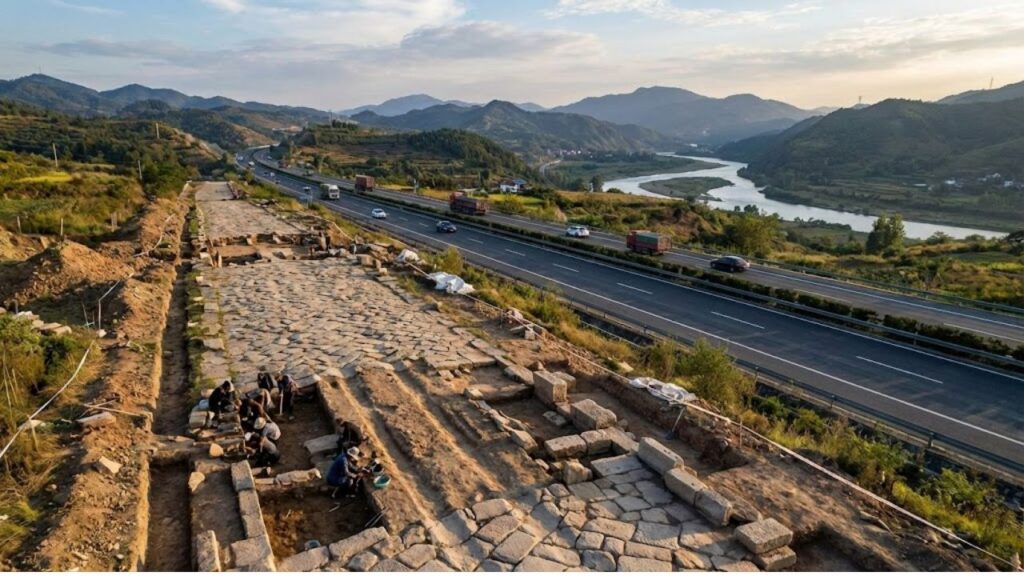

Researchers in China have uncovered a 13-kilometre section of an imperial road dating back over 2,200 years to the Qin dynasty. Located in Shaanxi province, the discovery forms part of the Qin Imperial Road, a strategic route that once stretched roughly 900 kilometres across northern China.

The discovery was released by the Yulin Cultural Heritage Conservation Institute and covered by regional media. Experts were struck not just by the road’s age, but by the advanced engineering methods used in its construction.

Cut in an almost perfectly straight line through challenging terrain, the road demonstrates a level of planning and earth-moving comparable to many modern highways. Excavations reveal deep trenches, massive tamped-earth embankments, and multiple compacted layers forming a solid surface capable of handling constant military traffic.

The roadway averages 40 metres wide and expands to nearly 60 metres in some areas, matching the scale of a modern multi-lane highway. Valleys were filled and ridges carved away to maintain straight alignment, a striking feat for a project begun in the early third century BCE.

A strategic artery of the first Chinese empire

Historical records describe the Qin Imperial Road as linking Xianyang, the Qin capital near present-day Xi’an, to Jiuyuan, close to modern Baotou in Inner Mongolia. The route ran along the frontier between settled farmland and the northern steppe regions.

The road was designed primarily as an instrument of state control, not commerce. It is attributed to Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of a unified China, whose reign from 221 to 210 BCE is known for sweeping centralisation efforts, including standardised laws, writing systems, canals, and early sections of the Great Wall.

Functioning as a mobile defensive barrier, the road enabled rapid troop deployment, swift delivery of supplies, and fast transmission of imperial commands to volatile border regions.

Accounts compiled by historian Sima Qian indicate construction began around 212 BCE and concluded by 207 BCE. Completing hundreds of kilometres of heavy earthworks in such a short period suggests a massive mobilisation of labour and resources.

Nearby excavations also revealed an ancient relay station used during both the Qin and Han dynasties. These facilities likely provided horses, food, lodging, and fresh officials, transforming the road into a high-speed communication network alongside its military role.

Second only to the Great Wall

According to China Cultural Heritage News, the Qin Imperial Road ranks as the second most important defensive project of ancient China, surpassed only by the Great Wall. While the Wall served as a static barrier, the road allowed the state to respond rapidly to threats.

This combination reflects a sophisticated security strategy: one structure delayed enemies, while the other enabled swift reinforcement. Together, they integrated frontier regions with the imperial core.

How modern technology revealed the lost highway

Although traces of the Qin road were first recorded in the 1970s, its full extent remained unclear until the use of remote-sensing technologies. Researchers combined satellite imagery, aerial photography, and field surveys to identify long, unusually straight alignments across hills and rivers.

Many segments, invisible at ground level due to farming and erosion, appear clearly from space. Subtle colour changes in satellite images often match buried embankments or compacted roadbeds on the ground.

To date, nine separate sections have been confirmed. Some survive only as hardened soil traces, while others still feature large raised embankments designed to keep the road dry and stable.

Ancient engineering compared with modern highways

Although traffic consisted of soldiers, horses, carts, and couriers, the underlying design principles mirror those used by modern civil engineers.

- Straight alignments reduced travel time and simplified navigation.

- Raised embankments protected the surface from flooding.

- Layered construction distributed weight and prevented deep ruts.

- Standardised width ensured predictable capacity for military columns.

Without asphalt or steel, Qin engineers relied on massive earthworks, simple tools such as wooden shovels and rammers, and a highly disciplined workforce.

The road typically measured 40–60 metres wide, comparable to many modern motorways. Its primary users were infantry, cavalry, carts, and couriers, and its core purpose was rapid military movement and imperial enforcement, rather than commercial transport.

What the Qin road reveals about early state power

The rediscovery reinforces the image of the Qin state as highly centralised and organised. Surveying and building across hundreds of kilometres required coordination between regions, reliable food supplies, and strict administrative control.

The road highlights how connectivity underpinned imperial authority. Administrative centres, frontier garrisons, and agricultural zones were bound into a single system. Orders could outpace unrest, and troops could arrive before rebellions spread.

As a result, the imperial road acted as a physical extension of the emperor’s reach, turning territory into governable space rather than abstract land.

For historians, the site provides rare physical evidence of early large-scale logistics. The nearby relay station offers insight into messenger routines, horse management, and staffing practices that written records only briefly describe.

Why the discovery matters today

The Qin Imperial Road adds historical depth to modern debates about mega-infrastructure projects in China. State-led construction, both praised and criticised today, has roots stretching back more than two thousand years.

There is also a cautionary contrast. The Qin dynasty collapsed only a few years after the road’s completion, underscoring the tension between engineering ambition and political stability.

Key ideas behind imperial road systems

Two concepts help explain the broader importance of the Qin road.

State capacity refers to a government’s ability to collect taxes, enforce laws, and execute complex projects. Long-distance roads and relay systems are strong indicators of high state capacity because they demand sustained coordination and funding.

Network effects describe how infrastructure becomes more valuable as it connects additional nodes. A single route between capital and frontier enables faster troop movement, while added branches to markets and ports can reshape entire regional economies.

For modern visitors, preserved sections of the road may become educational landmarks alongside nearby Great Wall sites. Walking the ancient alignment reveals the scale of the project, with towering earthbanks cutting straight through landscapes shaped by generations of farmers.

Archaeologists now face a familiar challenge: balancing preservation and development. Decisions made in Shaanxi and Inner Mongolia will determine whether this 2,200-year-old highway remains visible on the ground or survives only through satellite imagery and academic records.