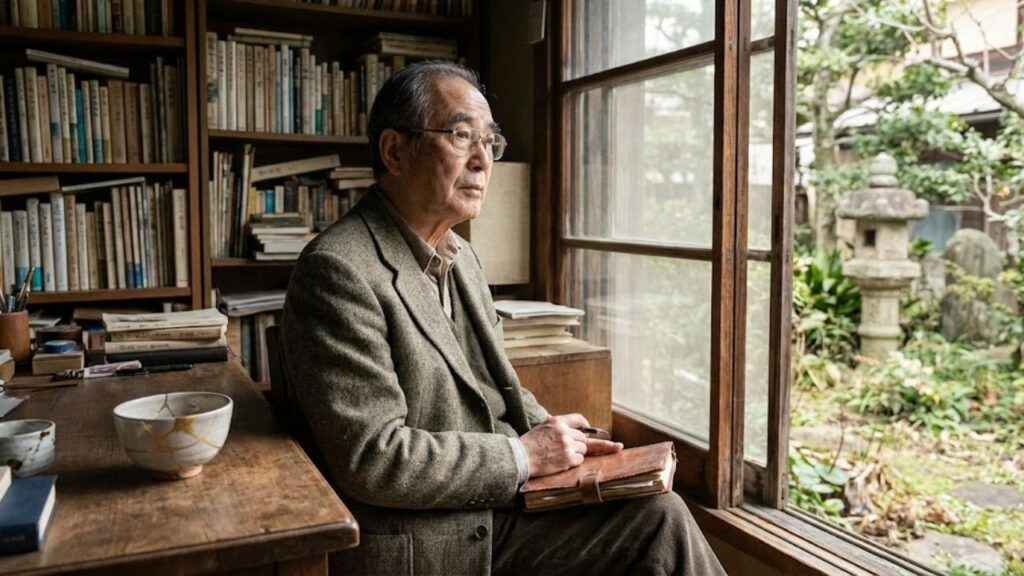

A world-famous therapist now suggests that a centuries-old Japanese idea may offer the most practical route to a calmer, more fulfilling life — not by chasing flawlessness, but by learning to live comfortably with imperfection, cracks, and uncertainty.

What this leading psychologist is highlighting

American psychologist Mark Travers, a therapist and frequent contributor to Forbes and Psychology Today, has closely followed the rapid rise of modern “life philosophies.” From toxic positivity to productivity-driven belief systems, many promise fast change. Yet, according to Travers, they often leave people feeling as though they are never doing enough.

He argues that wabi-sabi offers a fundamentally different approach: a way to feel emotionally grounded without pretending that life is neat, predictable, or painless.

Travers notes that people with strong mental health tend to share one key habit — they do not exhaust themselves resisting difficult experiences. Instead, they develop the ability to sit with discomfort, learn from it, and then move forward.

In his view, wabi-sabi is far more than a visual style. It functions as a psychological training ground, encouraging acceptance of loss, discomfort, and imperfection as natural parts of being human. That shift, he says, supports healthier emotional regulation than any “good vibes only” mindset.

Understanding what wabi-sabi really means

The concept originates in Japanese aesthetics and Zen Buddhism. While it has no direct English translation, it is generally understood as a combination of two ideas:

- Wabi — the quiet beauty found in simplicity and humility

- Sabi — the beauty that emerges through age, wear, and impermanence

Together, wabi-sabi values objects and experiences that are simple, natural, and gently worn. It rejects the belief that something must be flawless to deserve appreciation.

Within this perspective, a chipped cup, a weathered bench, or a wrinkled smile are not defects to correct, but stories worth preserving.

This outlook extends beyond objects. It also applies to zigzagging careers, relationships marked by scars, and bodies that change over time. Where Western self-help often labels these as shortcomings, wabi-sabi sees them as evidence of living.

- Bad news for people who call a handyman to clean their grout: he uses only 3 ingredients and in 15 minutes it looks like new – and that makes some furious

- Bad news for homeowners: starting February 15, a new rule prohibits mowing lawns between noon and 4 p.m.

- Aluminum foil in the freezer: the simple hack winning over more households

- Greenland declares an emergency after researchers spot orcas breaching dangerously close to rapidly melting ice shelves

- Goodbye pressure cooker as families move toward a smarter safer appliance that automates every recipe with ease

- Psychologists say people who prefer silence in the morning show higher emotional regulation

- Forget Burj Khalifa and Shanghai Tower: Saudi Arabia readies a 1km-tall skyscraper

- Scientists observe a sudden change in volcanic gas emissions without eruption signs

How a design trend became a way of living

For many outside Japan, wabi-sabi first appeared through social media interiors and carefully styled ceramics. This exposure has often blurred the line between a profound philosophy and a fleeting aesthetic trend. Still, researchers suggest the idea runs deeper than muted colours and textured surfaces.

A study published in Art and Society examined how wabi-sabi aesthetics intersect with Nordic minimalism in modern interior design. The researchers found that both styles prioritise open space, calm, and natural materials, though for different reasons.

Wabi-sabi embraces imperfection and the passage of time, while Scandinavian minimalism focuses on clarity and clean lines.

Together, these approaches have influenced how many people shape their homes and workplaces — fewer objects, more breathing room, and less visual noise. The study links this shift to mindfulness, tranquillity, and functionality, qualities closely aligned with modern mental health goals.

Why psychologists call it the most effective mindset

When Travers refers to wabi-sabi as the most powerful life philosophy available, he is comparing its psychological impact with that of popular Western success narratives.

Many modern philosophies centre on constant maximisation — earning more, achieving more, optimising more. They leave little space for illness, grief, or simply being ordinary. That gap between expectation and reality is often where anxiety takes hold.

Wabi-sabi narrows that gap by treating imperfection as the baseline, not the failure.

This perspective can support mental health in several ways:

- Lower perfectionism: mistakes feel less overwhelming when flaws are expected

- Greater resilience: accepting change helps people adapt to sudden shifts

- More authentic relationships: self-acceptance reduces harsh judgment of others

- Reduced comparison: focus moves from “best” to “true,” easing social pressure

From a clinical standpoint, this combination directly strengthens emotional regulation by encouraging awareness, presence, and flexible responses.

Ways to bring wabi-sabi into everyday life

Living with wabi-sabi does not require specialised rituals or new décor. It begins with small changes in how you approach your space, time, and inner dialogue.

At home

- Keep a few aged items — an old table or faded photo — where you can see them

- Release decorative clutter that lacks purpose or meaning

- Choose natural materials such as wood, linen, clay, stone, or plants

- Allow gentle imperfections, like uneven shelves or handmade objects

In your schedule

- Leave intentional empty space in your week

- Set realistic daily goals rather than heroic ones

- Build short pauses between tasks to reconnect with your body and breath

- Accept lower-energy days without labelling them failures

In your self-talk

Wabi-sabi also reshapes how you speak to yourself. Phrases like “I should be over this” assume life must be smooth.

This mindset replaces them with gentler alternatives: “This is messy, and that’s allowed,” or “I am still worthy here.”

Therapists often see this subtle language shift as a turning point for people struggling with shame or chronic self-criticism.

Simple practices to experiment with this week

Mental health professionals suggest approaching wabi-sabi through small, practical experiments:

- Crack appreciation: notice one imperfect object daily and name what you value about it

- One imperfect photo: take a single photo without retakes or filters and keep it

- Five-minute reset: clear one surface and intentionally leave open space

- Weather check-in: describe your mood twice daily like a weather report, without judgment

Key ideas behind the philosophy

Several psychological concepts closely align with wabi-sabi:

- Impermanence: recognising that jobs, bodies, and relationships change can reduce anxiety around loss

- Mindfulness: anchoring attention in the present moment rather than replaying or rehearsing

- Radical acceptance: choosing how to respond once you stop fighting reality

What a wabi-sabi day can look like

Picture a Monday guided by this mindset. You oversleep. Instead of declaring the day ruined, you adjust. A non-essential task is dropped, breakfast is simpler, and the slower pace is accepted.

At work, a presentation contains a typo. You correct it, offer a brief apology, and move on without spiralling. At lunch, you sit on a bench with peeling paint, noticing the marks left by time. That quiet attention pulls you away from constant performance tracking.

At home, you resist scrolling through images of perfect interiors. You tidy one corner, place a chipped mug you love on the table, and leave the rest for another day. Care remains — only the demand for perfection disappears.

Limits, risks, and realistic use

Psychologists caution against using wabi-sabi as a reason to disengage. Accepting impermanence should not become avoidance of responsibility or difficult conversations. The goal is active acceptance, not apathy.

There is also a cultural consideration. Wabi-sabi emerges from a specific Japanese context shaped by Zen practice and traditional arts. Stripping it down for commercial use can flatten its meaning. Mental health professionals recommend approaching it with respect and curiosity, rather than as another self-improvement label.

When used thoughtfully, wabi-sabi can complement therapy, medication, and other wellbeing strategies. It does not replace clinical treatment, but it can soften the harsh inner narratives that often accompany anxiety and depression.