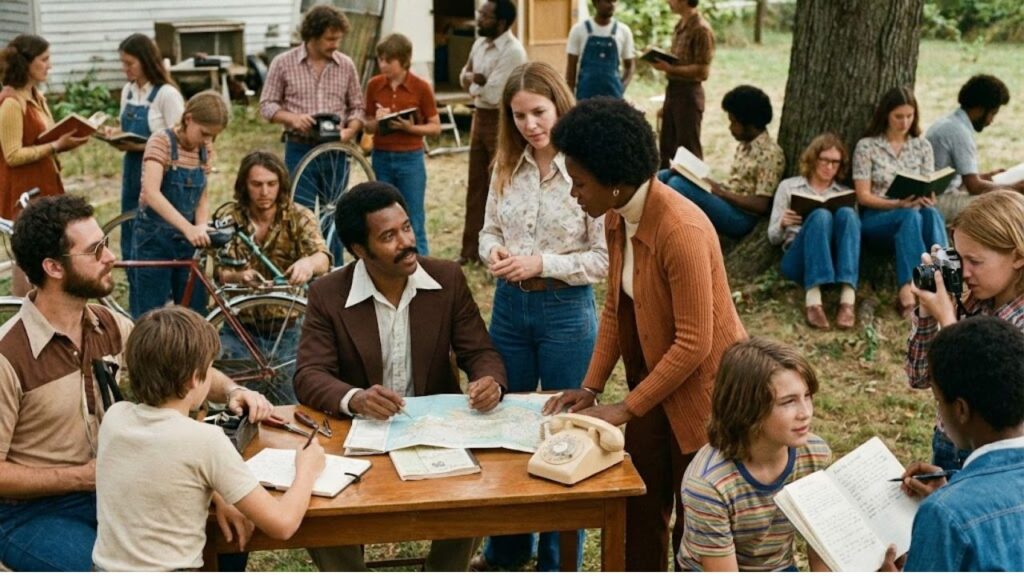

One evening in a busy café, an older man unfolded a paper map and calmly traced his route, while nearby teenagers argued with a frozen GPS screen. Same city, same street, but two very different reactions to surprise. At another table, a woman in her sixties waited for a late friend with no phone in hand, no restless scrolling, just relaxed patience. There was a steady, grounded confidence in her posture. Psychologists say moments like these aren’t random. They often reflect how earlier decades quietly shaped the mind.

Mental strengths shaped by growing up in the 60s and 70s

People who came of age during the 1960s and 1970s learned early that uncertainty was part of daily life. Buses didn’t arrive on time, plans fell apart, and parents were unreachable for hours. News traveled slowly, and answers required effort. Living inside those gaps didn’t just create memories—it trained the mind. Research on resilience, cognitive flexibility, and delayed gratification repeatedly shows that these environments encouraged mental traits that now feel rare in a constantly connected world.

Waiting as everyday mental training

In the early 1970s, hearing a favorite song meant waiting for it to play on the radio again or buying a record—if it was available. That repeated experience of wanting without instant reward strengthened what psychologists call delay of gratification. This ability is closely linked to emotional regulation, relationship stability, and long-term success. For that generation, patience wasn’t a strategy. It was routine.

How everyday friction built frustration tolerance

Queues for movie tickets, weeks spent developing photos, and months of saving for a single purchase all trained the brain to sit with discomfort. From a psychological perspective, this builds distress tolerance—the capacity to remain present even when things feel dull or frustrating. Many younger people now have to relearn this skill intentionally. For those raised in the 60s and 70s, it was simply part of life.

From rotary phones to focused attention

One striking ability from that era is the ease of true disconnection. Leaving the house once meant being unreachable. No alerts, no instant replies, no invisible conversations tugging at attention. Psychologists describe the result as attentional control—the ability to fully engage with where you are. While people weren’t consciously practicing mindfulness, the absence of constant interruptions made deep focus more natural.

Relearning the value of being unreachable

Recreating even a small part of that experience today can feel unsettling at first. Setting aside a daily hour without a phone often brings mild anxiety before calm sets in. The mind slowly relearns that nothing falls apart when responses are delayed. For many older adults, this isn’t a method—it’s simply called going for a walk. For younger generations, it often needs a name and a reminder.

At odds with the family, one heir refuses to see the notary: can the estate still be settled?

At odds with the family, one heir refuses to see the notary: can the estate still be settled?

The quiet strengths many don’t realize they have

People who grew up in the 60s and 70s rarely advertise these traits. To them, they’re just normal habits formed long ago. Psychologists frequently identify a similar group of abilities across studies:

- Frustration tolerance built through waiting and limited options

- Patience developed without instant results

- Face-to-face social confidence learned through real conversations

- Improvisation shaped by broken plans

- Risk assessment practiced without constant tracking

- Resourcefulness gained from repairing instead of replacing

- Political awareness formed through discussion, not algorithms

- Deep focus strengthened by fewer interruptions

- Long-term perspective built through saving and commitment

Old-fashioned doesn’t mean obsolete

A common misunderstanding is confusing old habits with useless ones. Learning from earlier generations doesn’t require rejecting modern tools. It means copying the structure, not the scenery. Choosing one task each week to do slowly—cooking from a book, writing by hand, learning without tutorials—adds small friction that trains the brain to stay engaged.

A bridge between generations, not a conflict

Psychology suggests that each era develops its own mental advantages. The 60s and 70s demanded patience, presence, and physical risk assessment. Today demands rapid information processing and complex social navigation. The real advantage lies in sharing, not competing. When generations exchange these strengths, they create practical ways to stay grounded in a fast, overstimulated world.

How mental strengths quietly pass on

These abilities aren’t transferred through lectures or nostalgia. They pass through small moments—an older person staying calm during a delay, a younger person noticing. In cafés, at bus stops, or around family tables, these lived examples quietly teach how to handle uncertainty. That’s how mental resilience moves from one decade to the next: naturally, patiently, and almost unnoticed.

Wrapping A “Jacket” Around Your Hot Water Tank Could Save £50–£60 On Your Energy Bill This Winter

Wrapping A “Jacket” Around Your Hot Water Tank Could Save £50–£60 On Your Energy Bill This Winter

| Key point | Detail | Value for the reader |

|---|---|---|

| Delayed gratification | 60s/70s childhoods required waiting, saving, and tolerating frustration. | Helps build self-control, stick with goals, and resist instant dopamine hits. |

| Deep presence | Growing up offline trained attention, patience, and face-to-face listening. | Offers a model for reducing stress and reclaiming focus in a noisy world. |

| Everyday resilience | Frequent small uncertainties nurtured improvisation and emotional toughness. | Provides concrete attitudes to handle modern crises without panicking. |