Just after New Year’s, envelopes began appearing on doorsteps across the country. Plain white ones — the kind most people associate with routine paperwork. Only this time, the message inside made hearts sink.

“Your state pension will be reduced by $140 per month starting with the February payment.”

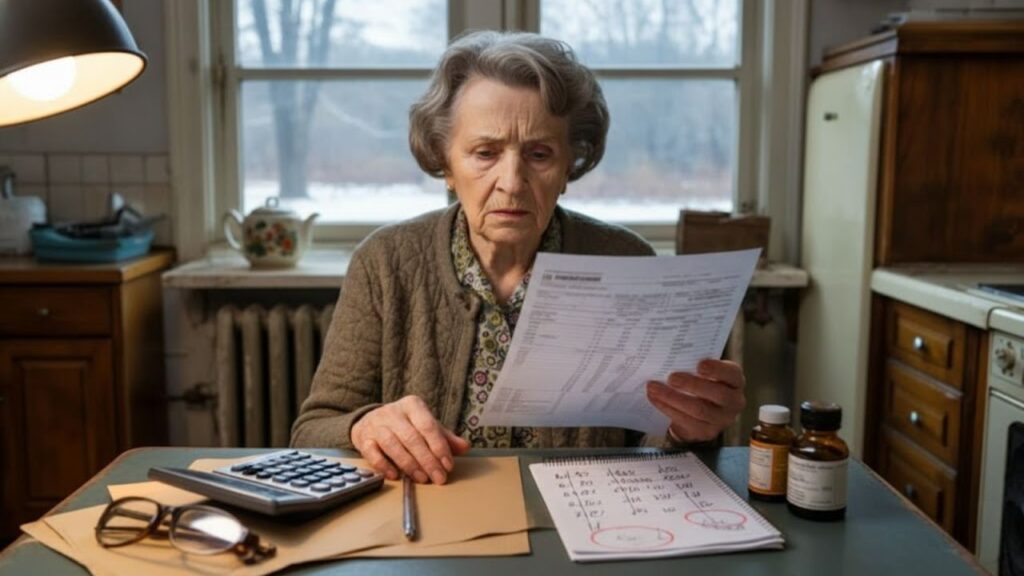

Mary, 71, sat at her kitchen table in Cleveland and read the sentence again. The kettle screeched behind her, but she barely noticed. That $140, she knew instantly, was food money. It was heating. It was prescriptions and bus rides to the doctor.

She picked up her phone to call her son, then paused. How do you explain that the cost of growing old has quietly gone up overnight?

Something fundamental has shifted — and it’s written clearly in that missing $140.

The real-world impact of a $140 monthly pension cut

On paper, $140 can look insignificant. A minor adjustment. A technical correction buried in a budget.

In real life, it’s the difference between a full grocery basket and an almost empty one. Between turning up the thermostat or staying wrapped in layers inside your own home.

All over the country, retirees are recalculating their lives at kitchen tables, on worn notebooks, and on cracked phone screens. Rent hasn’t dropped. Medication hasn’t become cheaper. And food prices keep climbing.

A February reduction hits especially hard. Winter is already when expenses peak, and this change lands right in the middle of it.

This isn’t abstract policy. It will show up in checking accounts — and in the daily choices people are forced to make.

Frank and Lila, both 68, live in a small apartment outside Phoenix. They retired early after years in retail, confident their combined state pensions would cover necessities while they picked up occasional part-time work.

They receive $1,350 a month. In February, that becomes $1,210. On their handwritten budget, that $140 represented breathing room — a modest emergency fund, one dinner out each month, and the co-pay for Frank’s inhaler.

Now that line is gone, and their routine is being rewritten.

Multiply their situation by hundreds of thousands, and the picture becomes clear: a slow, steady squeeze on people with no realistic way to recover the loss.

Why officials say the cut was unavoidable

Government officials describe the reduction as a “necessary recalibration” of public spending. The language is polished: long-term sustainability, demographic pressures, fiscal responsibility.

Behind those phrases is a straightforward reality. There are more retirees, fewer workers paying into the system, and rising costs tied to healthcare and social services.

From a spreadsheet perspective, trimming $140 from each pension looks like a simple fix — a way to stabilize the system for the future.

The danger lies in what those numbers mean off the page. When small cuts create large gaps in monthly survival budgets, trust in the system begins to erode.

How retirees are adjusting right now

For many, the first response has been blunt and practical: rebuilding the monthly budget from scratch.

No apps. No software. Just a pen, a notebook, and a bank statement.

Fixed costs come first — housing, utilities, insurance, essential medication. Then variable spending like groceries, transport, and small comforts.

Non-negotiables get circled. Everything else faces a tough question: “Can I live with less of this for the next few months?”

It’s uncomfortable, but identifying the shortfall before the account dips into the red restores a small sense of control.

Another crucial step is speaking up early — with family members, landlords, and service providers.

Goodbye Hair Dye for Grey Hair: The Conditioner Add-In That Gradually Restores Natural Colour

Goodbye Hair Dye for Grey Hair: The Conditioner Add-In That Gradually Restores Natural Colour

After a lifetime of working and contributing, admitting financial strain feels heavy. But those conversations can open doors.

Some landlords may allow flexible payments. Utility companies often have hardship options. Local pharmacies may know about discount programs people never realize exist.

Ignoring the problem rarely helps. Silence almost always costs more.

Small adjustments that make a real difference

Daniel Ortiz, a community financial counselor who runs free senior clinics, hears the same concerns every day.

“When you’re on a fixed income, every cut is permanent,” he says. “You don’t earn it back. You live with it.”

On the whiteboard in his office, he keeps a list of strategies that repeatedly help his clients:

- Reviewing prescriptions with a doctor or pharmacist to switch to generic medications

- Calling phone and internet providers annually to request lower-cost or loyalty plans

- Checking eligibility for every benefit and tax credit, even those assumed out of reach

- Sharing bulk grocery purchases with neighbors to reduce food costs

- Using senior centers for free legal and financial clinics, not just social activities

These small steps matter more when $140 disappears without warning.

What this moment says about aging and promises

A state pension reduction isn’t only about money. It’s about trust — the belief that decades of work and contributions would guarantee a basic level of security later in life.

For many retirees, that foundation suddenly feels thinner.

With February approaching, the countdown has begun.

Some will adapt by taking side jobs, renting out rooms, or postponing medical care — quiet sacrifices that never appear in official statistics.

Others have no flexibility left at all. For them, $140 marks the edge.

There’s also a psychological toll. People who once considered themselves retired now talk about returning to work at 70, 72, even 75 — not out of choice, but necessity.

Younger generations watching their parents navigate this are drawing their own conclusions. What was once seen as a stable guarantee now feels like a moving target.

The system isn’t collapsing, but it’s changing. Personal planning, once optional, now feels essential much earlier than expected.

The safety net remains — but with more gaps than many anticipated.

What happens next is still being written

The risk is that the conversation stalls between arguments about cutting spending or raising taxes, while those affected by February’s reduction quietly absorb the impact.

There is space for a more constructive response.

Mutual aid within communities, better outreach from local councils, and open family conversations about money can soften the blow.

Policy makers argue the $140 cut is required to protect the future. Retirees are left questioning why that protection so often arrives as immediate hardship.

In the coming months, resilience and solidarity will be tested.

What’s certain is that February’s payments will arrive $140 lighter. And one by one, people will decide what to cut back on, what to fight for, and who they can lean on as they adjust to a quieter but very real change in their lives.