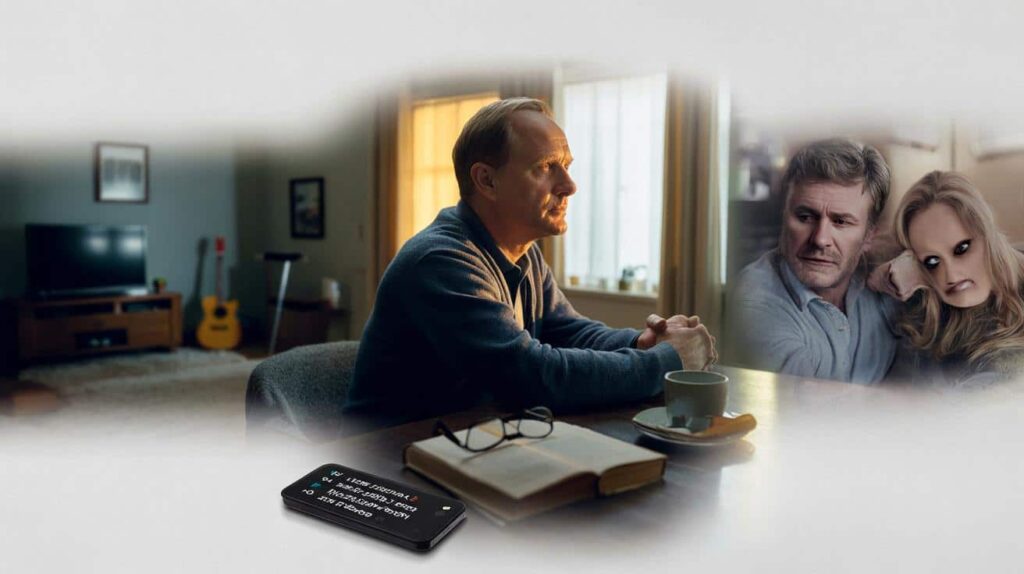

They just fade, year after year, until something vital seems missing.

He still goes to work, pays the bills, shows up at family events. But his spark is gone, his laughter rarer, his patience thin. Behind the routine and the steady exterior, a quiet kind of unhappiness is settling in.

The silent slide into joyless ageing

Across the UK, US and much of Europe, mental health data shows a similar pattern: many men reach midlife apparently “successful”, yet feel strangely empty. They do not necessarily drink heavily, shout, or vanish. They endure. They function. And they slowly stop feeling alive.

The most dangerous crisis for many men is not a midlife explosion, but a decades-long erosion of joy.

Psychologists point to a mix of social expectations, unexamined habits and small daily choices that quietly drain men of their capacity for happiness. These patterns rarely make headlines, but they show up in GP appointments, strained marriages and lonely retirements.

Here are 10 behaviours that often predict an older age marked by regret, isolation and a sense of having missed something crucial.

1. Letting friendships die

Many men are taught, subtly or bluntly, that friendship is optional. Work, mortgage and family take priority. Calling a mate just to talk starts to feel indulgent. Years pass. Messages stop. Weekends fill up with errands and screens.

The result is not just “being busy”. It is isolation. Research consistently links loneliness to higher risks of depression, heart disease and early death, especially for older men who live alone or rely solely on a partner for emotional contact.

Friendship is not a bonus for men; it functions like a protective layer against life’s hardest blows.

Men who nurture a small circle of honest, regular friendships in midlife are far more likely to report satisfaction and resilience in their seventies and eighties.

2. Pushing emotions underground

Boys still grow up hearing phrases like “man up” and “don’t be soft”. The lesson sinks in: emotions are dangerous, embarrassing, or a sign of weakness. So many men stop naming what they feel. Over time, they stop even recognising it.

That shutdown rarely looks like visible sadness. It appears as irritability, sarcasm, numbness, constant scrolling, long silences at the dinner table. NHS and US data both show men are less likely to be diagnosed with depression, not because they feel better, but because their distress does not match the cliché of tears and dramatic confessions.

When feelings are never expressed, they harden. Anger curdles into bitterness. Fear becomes control. Shame turns into withdrawal. The inner life shrinks until joy has no space to breathe.

3. Losing curiosity about anything new

One of the clearest warning signs of a quietly unhappy man is a shrinking world. He stops reading books, trying new routes, learning unfamiliar skills. He dismisses new music, new neighbours, new ideas as “nonsense”.

This is not just grumpiness. Curiosity keeps the brain flexible and gives each decade fresh material for meaning and delight. Without it, days blur. Conversations repeat. The future looks like a long replay of the past.

When a man stops asking questions, his life story moves from “ongoing” to “already decided”.

4. Tying self-worth only to work and productivity

For generations, men have been told their value lies in what they provide: salary, status, visible results. That script can be motivating at 30. At 60 or 70, it can be brutal.

Retirement, redundancy or even a simple change in role can feel like an attack on identity. Without a job title or a busy schedule, some men feel disposable. The danger is not just financial anxiety, but a belief that they no longer matter once they produce less.

Men who find roles beyond paid work — mentoring, volunteering, grandparenting, learning — tend to navigate later life with far more contentment.

5. Nursing old grudges for decades

A falling-out with a sibling, an unfair boss, a divorce that felt like betrayal: these are real wounds. But when anger becomes a long-term companion, it stains everything else.

Holding on to grievances offers a short-term sense of clarity: “I know who wronged me.” Over time, though, that story tightens. Family gatherings become minefields. New relationships feel unsafe. The future is seen mainly as a place where more people will disappoint you.

Refusing to forgive rarely punishes the other person. It shackles the storyteller to a single painful chapter.

6. Abandoning basic physical care

Another subtle slide appears in the body. The gym membership lapses. Walks get shorter. Meals tilt towards convenience. Check-ups are postponed “until things calm down”.

The body responds predictably: weight gain, poor sleep, joint pain, sluggish energy. Once everyday movement feels heavy, pleasure shrinks too. A day out with grandchildren, a city break, a simple stroll in the park start to feel like chores.

Men who keep even modest routines — daily walking, light strength exercises, stretching, regular health checks — often report better moods and sharper minds well into older age.

7. Skipping the hard conversations

Many men will discuss football, interest rates or the state of the roads for hours. Yet they avoid conversations about fear, regret, attraction, or disappointment. Those topics feel dangerous: they might trigger conflict, tears, or change.

The price is distance. Partners sense something unsaid. Children grow up unsure how their father truly feels. Friends remain “mates” but not confidants.

Being known — truly known by at least one person — is one of the strongest predictors of lasting happiness in later life.

When tough talks are postponed for years, they often resurface in crisis: affairs, sudden separations, estrangements that feel like they came “out of nowhere”. In reality, they were years in the making.

8. Building happiness on control

Some men only feel safe when everything goes according to plan. They manage the family calendar, correct minor mistakes, and react badly to surprises. Control becomes their main psychological tool.

Ageing makes that strategy impossible. Health changes. Adult children make their own choices. Technology moves quickly. The news cycle grows relentless. A man who cannot adapt ends up in a constant state of frustration.

Men who learn flexibility — sometimes accepting “good enough” instead of “my way” — tend to suffer less from stress and are easier to be around in older age.

9. Stopping visible affection

There is a quiet tragedy in the phrase: “They know I love them.” Many fathers, husbands and partners rely on that assumption. Over the years, the hugs get rarer, the compliments stop, the “I love you”s fade away.

Affection is not just a feeling; it is a behaviour. Without words, touch, or time given on purpose, relationships cool. Adult children call less. Partners feel taken for granted. Friends drift.

Expressing affection nourishes both sides: the person who receives it, and the man who remembers he is still capable of warmth.

10. Believing it is “too late” to change

Perhaps the most damaging belief of all is the quiet thought: “This is just who I am now.” At 50, 60 or 75, change can look naïve. New hobbies feel pointless, therapy embarrassing, apologies impossible.

Yet gerontology studies are clear: people can form new habits, repair relationships and build fresh sources of meaning well into their eighties. The brain stays more adaptable than many assume, especially when challenged.

Men who reject the “too late” myth are the ones you notice in later life: the grandfather taking piano lessons, the widower joining a walking group, the retired mechanic mentoring apprentices one afternoon a week.

Patterns that quietly reinforce each other

These behaviours rarely appear alone. They tend to cluster and amplify one another. A man who drops his friendships may also stop exercising, spend more time online, and feel less inclined to open up emotionally. The social, physical and psychological effects add up.

| Behaviour | Typical long-term consequence |

|---|---|

| Letting friendships fade | Increased loneliness, higher risk of depression |

| Suppressing emotions | Anger, numbness, relationship breakdowns |

| Abandoning physical health | Lower energy, less social life, reduced mobility |

| Avoiding hard conversations | Unresolved conflict, estrangement, distance from loved ones |

| Believing change is impossible | Fixed routines, regret, loss of hope |

Practical shifts men can try this week

Change does not need to start with a dramatic gesture. Small, repeatable actions often work better than grand promises. A few examples:

- Call one old friend and suggest coffee, a match, or a walk.

- Tell a partner, child or sibling something you appreciate about them, out loud.

- Book one health check you have been postponing.

- Spend 15 minutes on a new skill: a language app, a guitar chord, a simple recipe.

- Write down one resentment and one tiny step towards letting part of it go.

Each of these actions chips away at the habits that foster quiet misery. None requires a personality transplant. They do require the willingness to be slightly uncomfortable now for a greater ease later.

Scenarios that often trigger a turning point

Many men only reassess their patterns after a shock. A heart scare, a partner threatening to leave, a child saying “I never really knew you” — these moments can jolt someone out of autopilot.

Imagine a 62-year-old recently retired engineer. His days were once tightly scheduled; now they stretch, unstructured. He finds himself snapping at his wife, scrolling late into the night, ignoring invitations. He tells himself he is fine. Underneath, he feels useless.

If he keeps going, the risk is a lonely, health-compromised old age. If he pauses and names what is happening — loss of role, fear of ageing, lack of friends — he has options: community classes, part-time mentoring, counselling, or simply choosing to say “yes” more often.

The gap between a joyless old age and a meaningful one is often a series of small, stubborn decisions made in midlife.

These 10 behaviours do not guarantee misery, but they tilt the odds in that direction. Noticing them early — in yourself, a partner, a parent or a friend — opens the door to different choices and, over time, a very different later life.